- What happens in you when a challenge you did not foresee jumps into your path?

- How do you respond when you are asked a confrontational question?

- What goes off you in you when you are blindsided?

How you respond to these questions roughly corresponds to your response when unexpected opportunity finds you, when someone seeks your counsel, or if a well-executed project lands you in the spotlight. We are self-centered creatures and are intrinsically wired to try to look good, to want to win, to extract the most benefit for ourselves and those we love, and to want to control our circumstances, regardless of how positively we perceive them. These natural responses can short-circuit our discernment, however, and prevent us from reflection, analysis, deep thinking, and collecting wisdom. They don’t help the leader lead well.

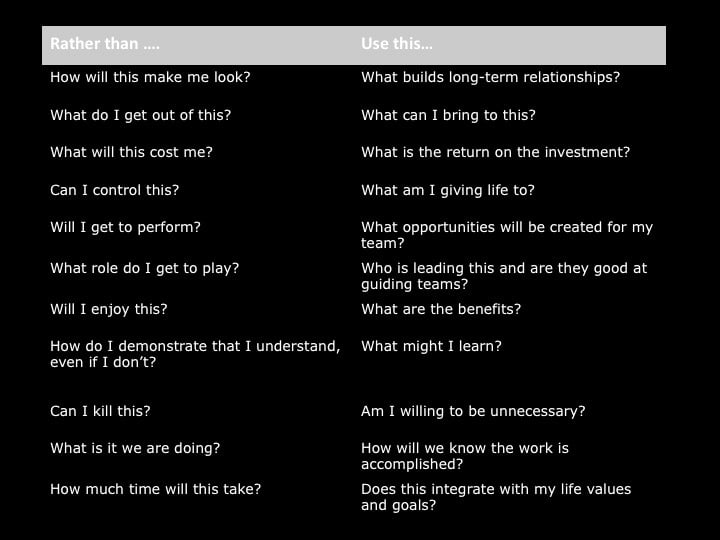

If you give this longer consideration you can begin to identify the questions that drive your initial responses to both challenges and opportunities. The reactionary set of questions tends to run as follows:

- How will this make me look?

- What do I get out of this?

- What will this cost me?

- Can I control this?

- Will I get to perform (with my knowledge or skill)?

- What role do I get to play?

- Will I enjoy this?

- How do I demonstrate that I understand, even if I don’t?

- Can I kill this?

- What is it we are doing?

- How much time will this take?

Effective leaders have to discipline themselves to a better set of baseline questions than these. This means wresting control of self from subconscious flight or fight reactions in favor of conscious, mission-supporting discernment.

Consider the following chart:

Disciplining oneself to respond with this more effective set of baseline questions involves trial, error, and refinement. It might feel like there is not enough time to function with this level of deliberation. However, reactive and rushed decision making tends to be self-centered, to create relationship messes, to miscommunicate, to foster poor teamwork, and to produce flawed results. Cleaning these up takes valuable time.

With practice, working from these new baseline questions becomes easier. They become familiar friends the leader wants to turn to. The process speeds up again as asking these questions become more natural, without the need to clean up messes.

If you doubt the benefit of slowing down enough to investigate your baseline questions and see what you might adjust, why not try the following experiment?

Pick a key challenge or opportunity. Edit a list of baseline questions you want to ask that are appropriate to the challenge. However awkwardly and stiffly it feels, work your way through them. Have them in front of you and make yourself thoroughly respond to each one. Don’t take shortcuts. Then ask, Is this better than rushing, reacting, lashing out, and becoming defensive?

I think you know the answer already!

Tags:

Mark L. Vincent, Design Group International, self-aware leader, Maestro-level Leaders, The Third Turn, Humble Leader

Post by

Mark L. Vincent

July 30, 2020

July 30, 2020

I walk alongside leaders, listening to understand their challenges, and helping them lead healthy organizations that flourish.

Comments