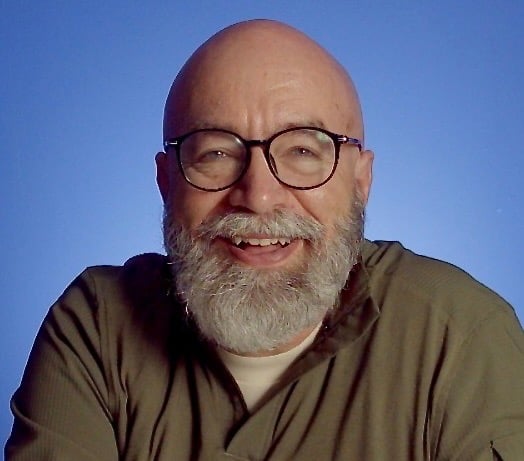

A true joy in this work comes from gleaning insight from people who are care to make a difference as they help organizations function effectively. Chuck Moyer is one such person, recently launching a franchise focused on helping to decrease vendor-related expenses that are all too often treated as fixed. In short, helping to improve that elusive mid-line. I spoke with Chuck Moyer about future value and the middle line.

First a bit of context then the five questions I asked him.

Part of Turn Two Leadership is learning to truly think like an Executive. This means being able to solve for long, middle and short term in combination with the top, middle and bottom line. Briefly stated, to be able to think in terms of time and money. This is a difficult skill to learn and seems to be increasingly difficult to find when recruiting executive leaders. If this is not mastered in the second turn of executive leadership, it becomes very difficult to enter into a fulfilling Third Turn journey as a Maestro-level leader.

If you like what you read below, you can reach out to Chuck as follows:

If you like what you read below, you can reach out to Chuck as follows:Chuck Moyer

P3 Cost Analysts

_________________________________

(mark l vincent): Two big mistakes seem to be made when looking for future value. The first is thinking that it must be about money, when in fact, future value essentially means more of the organization’s stated mission. Money may help to make that mission happen but it is a means, not the end. A second is thinking that where money is involved it must mean getting more of it rather than using it more wisely. You’ve built a career around wiser use of money, and now, at this stage of life are helping others get wiser. Tell us about it.

(Chuck Moyer): This is a subject I've thought deeply about recently. Early in my career I worked for two companies with a huge focus on developing people and solving customer problems. While both had financial goals and we planned toward them, I never felt these goals took precedent over doing the basic things for people and customers. I received a tremendous education from these companies. Both also created tremendous investor value. I think of this as my first career.

By contrast, my second career was primarily in private equity, turning low performing companies into high performing companies. We were charged with creating tremendous financial value in a very short time. We generally did this by changing the business model to provide dramatically greater customer value combined with more effective ways to market to drive growth. I had the opportunity to do this five times. We created tremendous customer value and shareholder value in general but the rate of growth also created customer and employee issues mostly related to turn over driven by the high rate of change. We left a lot of talented people behind because they couldn't grow up fast enough. Looking back, I believe more value could have been created by taking the time to fully think through the people and customer issues caused by rapid change and make sure they were covered before moving on. There are few financial people who would look at the value creation and think it was anything but spectacular, but as I reflect I think we could have done much better.

In this third career where I am now, I simply help people solve a problem they don't know they have. We don't charge up front and only collect a share of the result after the fact. This is pure customer value.

(mark l vincent): Can you tell us a couple of stories here: one where the client benefitted from this approach, and one where the client did not achieve the full benefit?

(Chuck Moyer): My first client saved $100,000 a year or a third of his merchant account spend. He had driven a great deal with his credit card processor but, like most people, didn’t understand how to optimize the interchange transactions behind the scenes. These invoices are highly detailed, long and complex. It takes a special skill set to address the problems.

There have been a few audits where we determined the client's spend was pretty close to optimal but none where they did not benefit in some way. They at least had peace of mind they were not overpaying and had paid nothing to find out.

(mark l vincent): What are the most consistent sources of the errors you find? How do they get introduced in the first place?

(Chuck Moyer) The most consistent source of error is human. The customer stops using a phone line and doesn't have it turned off. A company inadvertently has many different mobile configurations, a person at the utility makes coding errors. These errors add up and it is the responsibility of the customer to find them and ask for them to be fixed. However, the invoices are long, complex and full of codes. This is very difficult to do.

The second, unfortunately, is greed. Salespeople and utilities add charges and price increases above what would be considered normal. That is why a lot of invoices state that by paying the invoice you accept the charges as correct. I'd like to say this is uncommon, but it is more the rule than the exception in some industries.

(mark l vincent): How might a company go beyond recovery to become more preventative?

(Chuck Moyer): The "errors" creep back in. The best way we've seen is to have a specialist audit them on an ongoing basis. We operate on an initial 60 month term during which we audit the invoices each cycle. Most customers see what we do on their behalf and ask us to stay on past the term.

(mark l vincent): Can we tackle a longer-term and deeper issue – or at least touch on it? When I ask non-profit leaders about their organizational size, their answer is usually their expenses budgeted for the current fiscal year. When I ask a for profit leader that same question, their answer is usually their income from the past fiscal year. If I suggest that a better financial measure of size ties to top, middle and bottom lines, I get a lot of “yeah, yeah, of course” comments. And then I get this question: “what do you mean by middle line?” The service you provide helps to build and preserve that important middle line. What obstacles do you have to overcome to help clients understand this larger benefit beyond just thinking they’ll recover a few bucks?

One of the reasons this problem exists is that, while it can be a good sized chunk of money, it isn't big enough for most any company to put in the front seat. The dedicated specialized skills would cost more than the problem costs. Because of this most companies couldn't resolve the problem if it were top of mind. There are better places to spend the resource. Our resources are dedicated, fully utilized and we've developed specialized systems and processes to be able to address these issues for many, many companies at the same time. Therefore we can do it efficiently and profitably. It is all we do.

The biggest push back is that we charge too much. The second biggest push back is that their team can handle this. In every case when I come back a few months later the problem is still there. Even when the value proposition is free positive cash flow from a problem you didn't know you have and don't have the wherewithal to correct yourself, some people prefer not to get help.

Are you listening to the Third Turn Podcast? The latest episode features Todd Hartch on work and meaning.

Tags:

Process consultation and design, Mark L. Vincent, Design Group International, behavioral economics, Executive Development, The Third Turn, The Third Turn Podcast, Kristin Evenson

Post by

Mark L. Vincent

May 27, 2021

May 27, 2021

I walk alongside leaders, listening to understand their challenges, and helping them lead healthy organizations that flourish.

Comments